The end of work: which jobs will survive the AI revolution?

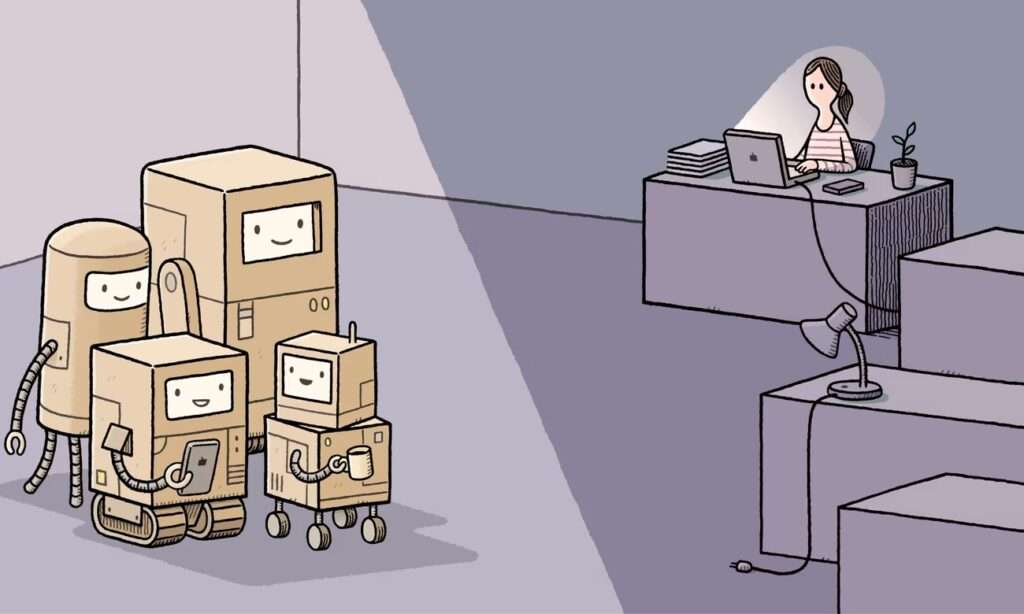

Smart machines are meant to work for us, but there are already signs that we will end up working for them. What will the workplace of the future look like, and will your role still exist?

At the 2021 Australian and US Open tennis championships, all the line judges were replaced by machines. This was, in many ways, inevitable. Not only are these machines far more accurate than any human at calling balls in or out, but they can also be programmed to make their calls in a human-like voice, so as not to disorient the players. It is a little eerie, the disembodied shriek of “Out!” coming from nowhere on the court (at the Australian Open the machines are programmed to speak with an Australian accent). But it is far less irritating than the delays required by challenging incorrect calls, and far more reliable. It takes very little getting used to.

In the slew of reports published in the 2010s looking to identify which jobs were most at risk of being automated out of existence, sports officials usually ranked very high up the list (the best known of these studies, by Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael Osborne in 2017, put a 98% probability on sports officiating being phased out by computers within 20 years). Here, after all, is a human enterprise where the single most important qualification is an ability to get the answer right. In or out? Ball or strike? Fair or foul? These are decisions that need to be underpinned by accurate intelligence. The technology does not even have to be state-of-the-art to produce far better answers than humans can. Hawk-Eye systems have been outperforming human eyesight for nearly 20 years. They were first officially adopted for tennis line calls in 2006, to check cricket umpire decisions in 2009 and, more recently, to rule on football offsides.

Yet despite the arrival of this smart technology, there are now many more people employed in sports officiating than ever before. Wimbledon has decided to retain its line judges, in part for aesthetic reasons. As the only major tournament played on grass, looking good against a green backdrop is a key part of the money-making machine (hence the requirement that the players wear nothing but white). The line judges are mainly there for their uniforms. In 2022, as for the previous 17 years, these were designed by Ralph Lauren.

Cricket matches, which traditionally featured just two umpires, currently have three to manage the complex demands of the technology, plus a referee to monitor the players’ behaviour, which still involves a large element of human discretion (who’s to say what is meant by “upholding the spirit of the game”?). Football matches have up to five officials, plus the large teams of screen-watchers needed to interpret the replays provided by the video assistant referee system (VAR). The NBA Replay Center at Secaucus, New Jersey, which employs 25 people full time, along with a rota of regular match officials, would not look out of place at Nasa.

Efficiency – even accuracy – turns out not to be the main requirement of the organisations that employ people to give decisions during sports games. They are also highly sensitive to appearance, which includes a wish to keep their sport looking and feeling like it’s still a human-centred enterprise. Smart technology can do many things, but in the absence of convincingly humanoid robots, it can’t really do that. So actual people are required to stand between the machines and those on the receiving end of their judgments. The result is more work all round.

Pour lire la suite de l’article, cliquez ici.

Source: Guardian News & Media, 19 août 2023 par David Runciman

Réponses